Bushfire protection

Key points

- Bushfire is a common event throughout Australia, affecting natural and built environments. The bushfire risk depends on climatic conditions, the local landscape, and the amount of vegetation available.

- The 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements identified that land-use planning and building regulations can influence the risk of exposure to natural hazards.

- Bushfire attack mechanisms include flame contact, ember attack, radiant heat, wind, and smoke. All of these can affect a building or building elements.

- Ember attack is the most common cause of building damage or destruction from bushfires. Embers can travel well in advance of the fire front, entering the home through gaps and igniting the building’s interior. They can also ignite debris on roofs, in gutters and windowsills or under raised floors.

- If you are building in a bushfire-prone area, you will need the bushfire attack level (BAL) of your house site assessed. This will tell you what level of design and construction you will need.

- Paying attention to siting, designing, and maintaining your home and surrounding area in relation to bushfire risk can significantly reduce the likelihood of bushfire damage. Key ways to reduce bushfire risk may include:

- simplifying your roof line and house outline, to reduce the opportunity for debris and embers to build up

- using appropriate non-combustible or low-combustible materials in construction

- ensuring gaps of no more than 2mm for all external openings

- establishing a clear asset protection zone with reduced fuel loads around your home.

- Ensure you have clear routes for evacuation, and for firefighting services to defend your home.

- Monitor fire danger throughout the fire season, and be prepared to leave early during bushfire conditions.

Understanding bushfires and homes

Bushfire has been part of the Australian natural environment for thousands of years. The bushland and grassland environments have adapted to fire, and some plants, animals, and ecosystems rely on bushfire for their lifecycles.

But bushfires can have devastating effects on human communities. Human and natural systems are damaged by frequent and intense bushfire, and many people have lost their lives, homes, businesses, and community infrastructure to fire. In January 2003, 4 people died and 470 homes were lost in the Canberra fires. During the Black Saturday fires of 2009, 173 people died. In the 2019–20 fire season, some 12 million hectares of land were burnt, 34 people died and over 3100 homes were lost (in more than 100 local government areas), with many more severely damaged.

The Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020) identified that “the likelihood of increases in the severity and frequency of natural hazards should be taken into account in land-use planning and building decisions”. Land-use planning and building regulations can influence the exposure of structures and communities to natural hazard risks.

Bushfire events vary greatly in impact. Most bushfires occur in the remote areas of Australia and have little impact on communities or people’s homes. However, in the south-east and south-west of Australia, bushfires tend to have higher impacts because many densely populated areas are close to bushfire prone areas.

Note

For decades, researchers have been looking at bushfire behaviour and why houses have been lost. Understanding bushfire risk and behaviour, and taking key steps in design and maintenance, can reduce your home’s bushfire risk.

Bushfire danger

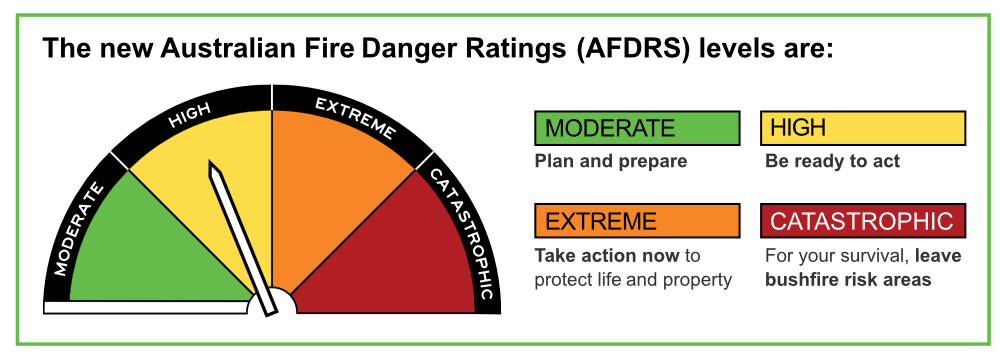

The Australian Fire Danger Ratings System (AFDRS) determines the Fire Danger Rating. Each Fire Danger Rating describes the consequences of a fire if one was to start and has specific action messages proportional to the risk, as displayed in the diagram. The white bar under Moderate, within the gauge component, indicates No Rating on days where no pre-emptive action is required by the community. This does not mean that fires cannot happen, but that any fires that start are not likely to move or act in a way that threatens the safety of the community.

The AFDRS Fire Danger Rating is based on Fire Behaviour Index values, which are calculated using bushfire behaviour models incorporating rainfall and drought conditions, local temperature, humidity and wind speed. Drought is a preconditioning factor for bushfire behaviour, whereas temperature, humidity and wind speeds are ambient conditions. Bushfires of low or moderate intensity often pose little threat to life, property and community assets. However, as fire danger increases bushfires can become impossible to control and the threat rises.

Source: © Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council (AFAC)

Bushfire seasons

Bushfires in the south-east and south-west of Australia are strongly associated with summer, whereas in northern Australia, the fire season is associated with the dry winter period. Each year, the bushfire season shifts from the north of the country to the south and starts again in the north each autumn. However, scientific research indicates climate change is making fire seasons longer each year (CSIRO and BOM 2020).

Source: Bureau of Meteorology

Bushfire ignition

The most serious of bushfires are more likely to be associated with lightning strikes during severe and extended drought. On an adverse fire weather day, storm fronts can bring lightning but little rain. Drought conditions such as high temperatures, low humidity, strong winds, and dried out fuel and soils, contribute to the spread and intensity of a bushfire. The worse the fire weather conditions, the more likely ignition and spread of fire will occur.

Many ignition sources for bushfires (about 80–90%) are related to human activity, such as arson, negligence, or deliberate burning off (Bryant C, 2008).

Bushfires and climate change

As our climate changes, we need to consider the future impact of potential bushfires and design our homes to be more resilient. Design for current bushfire conditions may need to be adjusted in the future. The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) has identified the major climate risks relevant to bushfire as:

- extreme heat – more frequent and intense extreme heat events throughout Australasia

- more dangerous bushfire conditions and increasing fire weather, particularly in southern and eastern Australia, and regions of New Zealand.

Shifts in climate may influence changes in the bushfire season and the frequency of fire weather events and fires across Australia. There is already a significant trend in some regions of southern Australia towards more days with weather conditions conducive to extreme bushfires (CSIRO and BOM 2020).

Bushfire behaviour

To understand how we can reduce the risk of damage to people’s homes, property, and assets of value (including the natural environment), we first need to understand bushfire behaviour. The term fire behaviour is used to describe the characteristics of a bushfire, including the rate of spread of a fire, flame heights and configuration, fire intensity, and the distances embers travel ahead of a fire, causing fires ahead of the main fire front.

The intensity of a bushfire, which determines to a large extent how much damage it will do, is a product of the:

- fuels burning (quantity, arrangement, size, moisture content)

- weather conditions at the time (temperature, wind speed and direction, relative humidity, atmospheric stability)

- topography of the land where the fire is burning (slope and aspect).

In an attempt to mitigate the effects of bushfires, hazard reduction burning (often referred to as prescribed burning) is used to reduce fuel levels within the landscape. However, the amount of fuel reduction that can be achieved in any given year is often limited by local weather conditions, which can be too wet or too dry; resources (people and money), which may be in short supply; the impact of smoke on people’s health or businesses (for example, smoke taint in grapes); or the environmental impacts of too frequent burning regimes.

As a consequence, the management of fuels close to buildings and infrastructure is often a more realistic option and may provide a more effective protection strategy than broad area burning.

Role of vegetation

Vegetation provides the fuel source for bushfires, however, not all vegetation is the same, and as a result, bushfires do not all behave in the same manner. Vegetation is classified into different types to generalise the fuel loads and the bushfire models used to determine fire behaviour:

-

Forests will typically have a shrubby understorey, sometimes in association with grasses, and are dominated by trees such as eucalypt, she-oak or cypress. Plantations of softwoods or hardwoods are treated as if they are also forests, although shrubs may be absent in some cases. Forested wetlands can be found along the coast or on inland waterways. Forest fires have extremely high flame heights, often involving the canopy, and can reach twice the tree height.

Forest with a shrubby understorey

Forest with a shrubby understoreyPhoto: Grahame Douglas

-

Woodlands differ from forests in that they are more likely to have a grassy understorey, with only a few, if any, scattered shrubs, and will generally have a more open canopy. Woodlands are generally dominated by eucalypts and may be located broadly from the coast to more arid landscapes. Woodland fires move faster than many forest fires because the canopy is more open and the wind can more readily flow through the stands of trees.

Woodland with grassy understorey

Woodland with grassy understoreyPhoto: Grahame Douglas

-

Shrublands and scrubs are dominated by shrubby plants, not trees, although some coastal scrubs may gain heights of 6m and may have a few isolated trees. Common shrubs include banksia, acacia, and tea-tree. In some environments, shrublands may be shorter (less than 2m) and can be associated with wetlands or coastal dunes and headlands. These communities are often referred to as heaths. They may be open where passage is relatively easy, or have thick closed canopies which are often impassable without walking tracks. Flame heights can be significant and may travel at greater speed than a forest fire, without the same heights.

Shrublands and scrubs

Shrublands and scrubsPhoto: Grahame Douglas

- Grasslands are found extensively across Australia and include large tracts of pasture and cropping areas associated with the ‘wheat belts’ of the mainland. Many of these grasslands occur as a result of the clearing of land for primary production, however, some native grasslands can be found. Grasslands are characterised by fast-moving fires, and flame heights can still be significant.

Photo: Grahame Douglas

Slopes and topography

The slope of the land has a significant effect on bushfire behaviour. Fires will typically run faster up a slope than on level ground, and experiments show that the rate of spread doubles for every 10 degrees of increasing slope and halves for every 10 degrees it runs downslope, relative to flat ground. With increasing slopes, fire behaviour increases with higher fire intensities and flame heights.

However, more complex landscapes can significantly affect this simple model. Complex topographical features such as gullies, saddles, and gorges all influence local winds and can shift the wind direction suddenly. In addition, winds do not blow in a consistent direction – a northerly wind can shift to a southerly. Winds can also exhibit lateral shift on the leeward sides of hills.

Tip

When considering building your home, it is important to consider local topography, slopes and prevailing wind directions. Always assume a bushfire will burn towards a building.

Bushfire attack mechanisms

Bushfire attack refers to the various methods in which bushfire may affect life and property. Flame contact, embers and burning debris, radiant heat, wind and smoke, can all affect a building either singly or in concert. The principles of bushfire protection need to address each of these bushfire attack mechanisms.

Flame contact

Flame contact refers to direct flame attack from the main fire front, where the flame that engulfs burning vegetation is the same as that which contacts the building. It is the highest level of bushfire attack.

Direct flame contact places significant heat stress on all aspects of a building’s construction. Flames can engulf and wrap around a building, exposing all sides and underfloor areas, as well as the roof, to overwhelming bushfire attack.

The flame front can directly contact a house if vegetation is close by. In some cases, ignition of the house can be from landscaping or other flammable materials close to the building. There may also be house-to-house (or garage-to-house) flame contact where a neighbouring house catches fire first and then affects the adjoining building.

Source: Adapted from NSW Rural Fire Service (2006).

Ember attack

Bushfires often generate embers, which can ignite buildings. Around 80% of houses lost can be attributed to ember attack, either alone, or in combination with other bushfire attack mechanisms, including radiant heat.

Embers may travel a long way in front of the fire front and may still be generated long after the main fire front has passed. Embers can be lofted into the air and fall when wind speeds drop.

Embers can gain entry through gaps in a building’s façade. Strong winds can push embers through narrow gaps, under doors, or ignite materials in the underfloor area of a building. Embers can build up on windowsills where they can ignite wooden frames or break the windows and ignite debris within gutters, allowing embers or flames to enter a building. Embers may also ‘flow’ along the ground and find entry points under doors, in roof spaces, or lodge in underfloor areas.

Embers can also ignite outdoor elements (for example, welcome mats, outdoor furniture) which can create more embers in the area. If the elements are close to windows, the windows may break and allow embers or flames into the home.

Radiant heat

Bushfires generate significant amounts of radiant heat. Measured in kilowatts per square metre (kW/m2), radiant heat is the heat energy released from the fire front that radiates to the surrounding environment, deteriorating rapidly over distance.

Radiant heat can cause a build-up of heat inside a building. This can cause fabrics and other combustible materials to ignite, even without any embers present. Fabrics will typically ignite at radiant heat levels of 10kW/m2 or less, and some low-density timbers may ignite at about 12 13kW/m2.

Radiant heat can also damage building materials such as window glazing. Single-glazed float glass typically cracks at about 12.5kW/m2, but covering float glass with a metal flyscreen can improve its performance to about 19kW/m2. Toughened glass can perform better than float glass as long it does not have direct flame contact from burning debris, when it can fail catastrophically.

Source: Adapted from NSW Rural Fire Service (2006).

Fire-generated winds

Bushfires under extreme conditions can generate their own weather conditions. Increased wind speeds are associated with an approaching fire front. In these extreme conditions, pyro-convective plumes or clouds can be formed giving rise to high pressure downdrafts or rotating plumes which can topple buildings, remove roofs, and break windows. Fire balls and fire tornadoes may occur causing heavy debris to ‘fly through the air’ or snap trees, which can fall on roofs or through walls and windows of a building.

Buildings built in bushfire prone areas may be subjected to high wind speeds caused by severe bushfire events. Therefore, it may be practical to design these buildings to cyclonic standards even if they are located in non-cyclonic zones. You can learn more about construction requirements in high-wind areas in the Australian Standards.

Smoke penetration

Smoke is an obvious aspect of bushfires and can enter buildings. Even if the building escapes ignition, the effects of smoke can often require replacement of many indoor furnishings. In addition, if occupants are still at home, smoke can affect breathing and vision.

It is important that living spaces within buildings restrict the entry of smoke. Measures typically used to improve energy conservation and efficiency also reduce the intrusion of smoke arising from a bushfire. The sealing of windows, doors (such as draft excluders) and other gaps will all help to reduce smoke and ember entry.

Source: Adapted from NSW Rural Fire Service (2006).

Designing for bushfires

There is no single strategy to protect life and property from the effects of bushfires. Bushfire protection measures should reflect the anticipated level of bushfire attack and work in combination with each other. Bushfire protection measures include:

- house siting and design

- separation of the structure from the bushfire hazard with asset protection zones

- access for firefighting and evacuation

- landscaping

- water supplies and other utilities.

When designing for bushfire protection, consider the likely bushfire risk and attack level for your home based on local fire weather conditions, fuel characteristics, and the slope or topography of the land surrounding the building.

New buildings, built to Australian Standard AS3959:2018 Construction of buildings in bushfire-prone areas, can reduce the risk of ignition. However, these houses may still be susceptible to bushfire attack depending on the fire, weather, landscaping, and owner behaviour. Building to the current standard cannot guarantee that a home will survive a bushfire event on every occasion. Many older buildings (pre-1991) are not built to AS 3959 and are particularly vulnerable to bushfire, but with well-considered renovations the risk can be reduced.

Siting of buildings

When deciding where to place your house site on the block, consider the topography and slope of the block, and how far away from any bushfire hazard the building can be located, as well as how you may evacuate in a bushfire emergency.

Topography

Houses should, as far as practical, not be located above a bushfire hazard. Instead, they should be located towards the base of any hill, remembering that fires increase in intensity up a slope. Saddles in the landscape should always be avoided as they are above a hazard and will funnel winds, promoting higher wind speeds.

Where houses are built on sloping ground, the cutting into the hillside facilitates the use of slab construction, rather than elevated floors that will capture radiant or convective heat underneath. If elevated (or cantilevered) floors are used, the cost of constructing for bushfire protection could be increased.

Access for firefighting and escape routes

Siting should facilitate the movement of people away from any bushfire hazard, as well as being as far from the hazard as possible.

In rural situations, it is vital to have a suitable roadway within your property that is in good condition, and is less than 200m from a public road. This will ensure fire fighters can access your property, and you can easily evacuate to safer locations.

Firefighting vehicles are usually about 3.5m wide (at the mirrors). An access road of 4m in width, with an additional 1m cleared area on each side, is recommended (check with the fire service in your state). If distances exceed 200m you should also incorporate passing bays. Overhanging branches across the access road should be cleared to a height of 4m to allow for the height of a firefighting vehicle.

Within the property, you should also ensure that there are suitable turnaround areas for fire trucks. A loop road around the house is best.

Access is also required to ensure firefighters can locate and use water supplies, whether it is mains water or a static water supply such as a tank. Ensure correct fittings and ease of accessibility for property protection during a fire by checking with your state or territory fire service.

Design and construction of buildings

If properly designed and maintained, buildings can shelter residents during the passage of a bushfire and allow fit and well-prepared people to defend their homes from any local ignitions. However, it is always considered the safest option to leave early.

The National Construction Code (NCC) developed by the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) contains the construction requirements for building within a designated bushfire-prone area.

For Class 1 buildings (residential houses), Class 2 buildings (for example multi-residential units), and Class 3 buildings (for example boarding houses, hotels or motels) performance requirements specify that the building must be designed and constructed to reduce the risk of ignition from a bushfire.

The NCC also references construction standards that provide the ‘deemed to satisfy’ or recipe solutions when building in a bushfire-prone area. In some jurisdictions nursing homes, schools, child care and health care buildings are also subject to these provisions. These standards are:

- Australian Standard AS3959:2018 Construction in bushfire-prone areas

- National Association of Steel Housing (NASH) Standard 2014 Steel-framed housing in bushfire areas (for Class 1 residential houses only).

Bushfire attack levels

A key aspect of both construction standards is the requirement to determine a building’s bushfire attack level (BAL). A building’s BAL is used to establish the requirements for construction to improve protection of building elements and to understand the radiant heat exposures for people in the open.

Potential housing sites should be individually assessed to determine their BAL rating. The current standard (AS3959:2018) provides the basic methodology for determining a BAL based on regional fire weather, vegetation class, slope and distance from vegetation. You should obtain the assistance of a suitably qualified bushfire practitioner to determine the BAL rating for your site.

Bushfire attack levels

| Bushfire attack level | Radiant heat flux exposure | Predicted bushfire attack mechanism | Building and material requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAL – Low | Not applicable | Nominal risk | There is insufficient risk to warrant specific construction requirements Most materials OK |

| BAL – 12.5 | <12/5kWm2 | Ember attack | Ember protection required Most materials OK |

| BAL – 19 | >12.5kWm2 – <19 kWm2 | Increasing levels of ember attack and burning debris ignited by windborne embers, together with increasing radiant heat flux | Ember protection required Slightly limited material choices |

| BAL – 29 | >19kWm2 – <29kWm2 | Increasing levels of ember attack and burning debris ignited by windborne embers, together with increasing radiant heat flux | Ember protection required Limited material choices, glazing requirements increase |

| BAL – 40 | >29kWm2 – <40kWm2 | Increasing levels of ember attack and burning debris ignited by windborne embers, together with increasing radiant heat flux with the increased likelihood of exposure to flames | Strong ember protection required Very limited material choices, strong glazing requirements |

| BAL – Flame Zone | >40kWm2 | Direct exposure to flames from the fire front, in addition to radiant heat flux and ember attack | Special construction details apply, full shielding required to glazing |

Note: kWm2 is heat flux density measured in watts per square metre.

Source: Adapted from Australian Standard AS3959:2018

Building elements

The following areas are addressed in the standards and should be considered for the assessed BAL rating of the building:

- subfloor supports if not enclosed

- floors, but slabs on ground have no requirements

- walls including up to 400mm from the ground

- external glazed elements (doors and windows)

- roofs including penetrations, guttering, gables, eaves, and fascias

- verandahs, decks, steps and landings

- water and gas supplies.

One of the key considerations in the standards is preventing the build-up of debris (that is, flammable material) and embers.

Some design features that are not part of the standards include simple rooflines and building outlines which can aid in the removal of debris and help to prevent the build-up of embers. Avoid complicated or saw-tooth roof lines. Reducing the number of re-entrant corners on a façade will also reduce the accumulation of debris. Also take care with gutter design. Avoid box gutters, and consider including non-combustible gutter guards to prevent leaf and other litter on roofs.

Source: Adapted from Ramsay and Rudolph (2003)

Photo: John Caley (Ecological Design)

On steeper slopes the underfloor area can be particularly vulnerable, with flames and convective heat attacking the underside of the flooring system. Enclosure of subfloors is therefore crucial in these conditions.

Other design features can include courtyards and barbeque areas that provide shielding to the main building façade and can be constructed of masonry or other non-combustible materials. Where outside roofed areas such as pergolas are planned, ensure that the roof trusses are placed external to the main building, rather than set within the roof space of the main building. Fascia can also incorporate fibre cement sheeting or metal to separate combustible timbers from additions or extensions to the main building.

Materials

The choice of materials including glazing, timbers, fibre cement sheeting and other materials is an important consideration when building in a bushfire-prone area.

Most materials on the exterior of buildings will need to be non-combustible or fully tested to the appropriate standard or compliance requirement for safe use. For example, double brick will provide better fire protection than weatherboard or brick veneer on a timber frame. There are a lot of materials and assemblies in the market that are promoted as suitable for use in bushfire protection that cannot provide acceptable evidence of the claim. Seek advice from your jurisdictional regulators.

Window glazing should be a high-performance toughened glass. Screening toughened glass improves its performance and can help keep debris away from the glass. Window and door frames should be selected and installed to reduce ignition potential or gaps that allow embers into the home. Using a windowsill with a steep slope also helps to keep debris away from window ledges.

Wall and ceiling insulation should be non-combustible. Materials inside a home can also pose a risk if they are toxic when heated or burned, so non-toxic paints, wall linings, floor coverings and other materials are recommended.

Pay attention to your emergency exit route. Decking, stairs, façades, and doors that are combustible can be a threat to safe evacuation.

Detailing

To prevent embers entering the building, gaps need to be sealed. All gaps in the building including vents, weepholes and joints are to be less than 2mm (AS3959:2018).

Flyscreen materials can reduce ember entry sizes in subfloor spaces and windows. Flyscreens may be aluminium, bronze, or corrosion resistant stainless-steel, dependent on the BAL, but cannot be plastic or fibreglass. Flyscreen materials must also have an aperture of less than 2mm.

Non-combustible building membranes (sarking) can provide secondary protection for walls and roof spaces. Australian Standard AS 3959:2018 specifies building membranes with a flammability index of less than 5. However, testing has shown that breathable non-combustible membranes are more effective and will withstand a greater level of heat exposure. Incorrectly specified and installed non-combustible membranes can lead to condensation issues.

Windows and doors are to be sealed when closed (conforming to Australian Standard AS2047 Windows and external glazed doors in buildings) and draught excluder used for any gaps.

Bushfire shutters may be used for window or door protection for the various BALs, however:

- they must protect the entire assembly (including frames, stills and glazing)

- materials must be consistent with the BAL requirements

- they must be fixed to the building and not be removable

- they must be manually operated at the building (inside or outside) and any motorised system must have back-up power supply, rather than mains power alone

- gaps in shutters should not be greater than 2mm but the surface may be perforated up to 20% of the overall shutter surface.

Condensation

Many of the most highly prone bushfire regions are also in climate zones that have cold winters. Requirements for bushfire construction and building methods to improve energy efficiency mean greater care is needed in building design and construction to reduce moisture-related problems such as mould, mildew and fungal growth. Refer to Condensation for more information on how to reduce the risk of condensation in your home.

Planning and building approvals

If you are intending to build a new home, you may require planning approval prior to obtaining the necessary building approval. The planning provisions are different for various states and territories. In addition, each state has different planning requirements for bushfire-affected areas.

All states and territories require compliance with the National Construction Code (NCC) which includes requirements for new buildings and certain alterations or additions to existing buildings in bushfire-prone areas.

Although the NCC is a nationally consistent code, there are some situations where a state or territory enforces a variation, addition or deletion to it.

It is recommended the NCC be read in conjunction with the relevant state and territory legislation. Any queries on such matters should be referred to the state or territory authority responsible for building and plumbing regulatory matters.

When planning to build a home in a bushfire-prone area, you should consider the use of a qualified bushfire planning practitioner to assist in the assessment of the BAL rating and planning requirements for your state.

Surrounds and landscaping

The area surrounding your home can be key to bushfire safety. Well-designed surrounds can support easy exit in an emergency and allow access for fire-fighting services. The siting, selection, and maintenance of landscaping can also have a significant impact on the vulnerability of a building to bushfire.

Asset protection zones and defendable space

The area surrounding your home is sometimes called an ‘asset protection zone’, where the main purpose is to prevent direct flame contact on a building. It can also be called ‘defendable space’, where the main purpose is to facilitate firefighting. The terminology can be interchangeable and may vary within different jurisdictions.

Asset protection zones provide a buffer zone between the building and the bushfire. Placing your home within a wide asset protection zone reduces the chance of the fire front reaching the building. An asset protection zone and defendable space should have minimal levels of combustible material, and clear wide paths for people and vehicles. The size of the zone required depends on the local conditions, including slope of the area, the type and structure of nearby vegetation, and whether the vegetation is managed. The NSW Fire Services has developed standards for asset protection zones [PDF].

Construction standards (and costs) are likely to rise with increasing BAL (especially flame contact and higher radiant heat). However, you can help reduce your BAL rating by making an allowance in your budget for a larger asset protection zone (separation from the hazard).

During a bushfire, fire fighters need a workable area around a building to extinguish burning debris or elements of a building. It is worth bearing in mind that fire fighters are likely to be allocated where they will be most effective at protecting lives and defendable property, not necessarily where property losses are most likely. Firefighting resources are unlikely to be allocated to property and assets that cannot be defended safely.

A defendable space also allows for residents who have been sheltering within their home to evacuate into a safer environment once the fire front has passed.

Source: Country Fire Authority Victoria

Landscaping

Typically, landscaping is not used to determine the BAL of a building, but poor placement and maintenance of plantings and other landscaping features can compromise what is otherwise a good design and well-constructed building.

Sustainable landscaping can help protect your home from bushfires:

- Avoid using highly combustible mulch.

- Use hard surfaces closer to the house.

- Avoid planting trees that will grow tall close to the house.

- Remove undergrowth where it could become a fire risk.

- Consider making fire breaks, especially in the path of likely fire spread.

- Ensure that all fencing close to the building is non-combustible, and easily maintained.

Water and other utilities

Water is essential for firefighting and property protection. Water may come from the mains water supply or from property water supplies (for example, tanks or dams).

Typically, urban pumper units will carry a small amount of water and rely on the mains supply whereas rural brigades have tankers which can carry up to about 3 000L of water. Even in areas with mains supply, you can consider adding a dedicated water supply to support firefighting during a bushfire event.

A recommended approach for rural areas is a water supply in which a dedicated amount is stored for firefighting and the remainder can be used for household use. This can be achieved by placing household and firefighting access fittings at different levels of a water tank. Multiple tanks are also an option. Firefighting fittings should comply with your state or territory requirements.

The amount of water recommended for firefighting may be provided by your state or region. You should also consider the building together with the expected duration and rate of use. Additional water will be needed if using a water spray or suitable drenching system.

Bushfire sprinkler systems

A sprinkler system may be used to wet down your home in advance of a fire. A sprinkler specialist familiar with Australian Standard AS5414:2012 Bushfire water spray systems should be consulted when designing this system.

You will need to carefully assess how a sprinkler system would be used, and how well it suits your circumstances. Sprinkler systems often require activation not too long before the fire reaches your home. If you need to be in place to activate it, this may prevent you leaving early. Some more modern systems may allow activation remotely by phone.

Note

You will also need to consider power supplies, as mains power can often fail during a bushfire and so water pumps may not work. Sprinkler systems use large amounts of water and will need very regular testing and maintenance.

Most systems are placed on the roof while some systems can be placed around the home to dampen surrounding landscaping and vegetation as well as the building. A spray system has finer droplet sizes than a drenching system. Fine droplets can be carried by the wind associated with a bushfire rendering it less effective. A drenching system has heavier droplets but can use more water, and has to be targeted specifically to the building element being protected.

Other utilities

It is important to remember that mains power can often fail during a bushfire, so you may need alternative sources of electricity if you are expecting to run systems such as water pumps. Solar power or generators may be an asset in the event of bushfire. Batteries should be stored away from the house if not properly enclosed.

Gas is a clear risk during fire, and you may wish to avoid connection to mains gas or the use of gas bottles.

Services such as power and gas should also be located so as not to contribute to a house fire. Gas cylinders, if used, should be located well away from the building and be screened from any potential bushfire. Relief valves should be positioned to vent away from the building.

Retrofitting and other protection measures

Many older houses were built without any bushfire protection measures, which makes them vulnerable to bushfire attack. If you have an older home, consult a bushfire construction expert for advice on retrofitting to make it more resilient to bushfire attack.

When considering retrofitting for bushfire protection, there are 3 major considerations:

- the costs of retrofitting – your budget

- the environment in which you are located – what is the bushfire risk?

- the effectiveness of the retrofit – any retrofit should address the key bushfire attack mechanisms of flame contact, embers, radiant heat, and wind.

You will need to balance costs against likely risks and benefits. It can be a good idea to investigate low- or medium-cost options, especially if you are in a low-risk area. Remember that when considering retrofit solutions, they may provide an opportunity to improve the performance of the building, but do not guarantee its survival.

The Victorian Building Authority’s Guide to retrofit your home for better protection from a bushfire [PDF], provides various options. Of course, another option is to retrofit entirely in accordance with the relevant standard (for example, AS3959:2018) and the level of bushfire risk that you face.

Low-cost options

The following items are low-cost measures:

- sealing all gaps around the house with appropriately-specified joining strips or flexible silicon-based sealant

- installing appropriately-specified building membranes behind weatherboards or other external cladding when they are being replaced

- installing appropriately-specified building membranes beneath existing roofing (especially tiled roofs) when it is being replaced for maintenance

- installing draught excluders at the base of side-hung doors, and draught seals around window and door frames

- sealing vents and weep holes in external walls with aluminium mesh (<2mm gap)

- sealing around roofing and roof penetrations with appropriately-specified flexible silicon-based sealant

- installing non-combustible gutter guards

- putting non-combustible metal mesh over areas of windows and doors where they can be opened

- reducing the amount of bushfire fuel around the house to create an asset protection zone or a defendable space.

Photo: AdShutters Pty Ltd, Adam Page

Medium-cost options

The following items are medium-cost measures:

- installing BAL compliant shutters or metal fly screens to doors and windows

- replacing or over-cladding parts of door frames less than 400mm above the ground, decks, and similar elements or fittings with metal or fibre-cement sheet (or both)

- applying intumescent (fire retardant) paints to timber features (especially under-floor or under-roof areas) noting that all paints will wear over time and require repainting regularly

- moving sheds and other external structures away from the house (ideally more than 6m away if you have room)

- replacing decking with non-combustible material such as fibre cement sheet

- fully enclosing subfloors with aluminium mesh (<2mm) or vented fibre-cement sheeting (using mesh or sealant for any gaps).

High-cost options

The following items are high-cost measures:

- installing a sprinkler or drenching system made of metal fittings and pipework (do not use plastic) using additional dedicated water (this system is best installed by a bushfire practitioner)

- replacing existing glass with laminated or toughened glass (note that debris should not be able to accumulate) in windows

- replacing wall and fascia with non-combustible or bushfire-resistant materials

- replacing tiled roofs with sheet metal with appropriately-specified building membrane or insulating blanket material ensuring all end of sheets are sealed to prevent ember entry

- installing appropriately-specified building membrane behind weatherboards or other external cladding and under tiled or sheet roofs when they otherwise would not have been replaced

- redesigning rooflines to remove box guttering and installing sheet metal or fibre-cement sheeting to lower sections of walls or re-entrant corners

- also implementing the medium-cost measures identified previously.

Preparing for bushfires

Bushfires require planning for your household and the community.

Maintenance and preparing for the bushfire season

Maintenance is crucially important to the integrity of the building as well as your survival. Check and prepare your home every year before the fire season. Your checks and maintenance should include:

- checking the exterior of your home for damage and gaps – check tiles and roof lines for broken tiles or dislodged roofing materials – check that screens on windows and doors are in good condition without breaks or holes and frames are well fitted into sills – check external wall surfaces for decaying timbers ensuring there are no gaps where embers can lodge – check doors are fitted with draught seals that are in good condition.

- checking your water supply – check pumps and water supplies are available and in working order – check that hoses and hose reels are not perished, and fittings are tight and in good order – test drenching or spray systems.

- removing combustible materials – clear leaf litter and debris from the roof and gutters – trim trees and other vegetation in the vicinity of the house – move woodpiles and other combustible materials well away from the house – check mats are of non-combustible material or in areas of low potential exposure – check driveways are in good condition with vegetation not too close to the edge of the roadway.

Personal safety

Everyone who lives near bushland should prepare a bushfire survival plan before the fire season. Those with an existing plan should review it and ensure it is still suitable for your current situation. Guidelines for the preparation of bushfire survival plans can be found on all state and territory fire service websites. An example of a bushfire survival plan can be found on the NSW Rural Fire Service website.

The plan should take into account your surroundings (whether you live in bushland, near the coast, on a farm, and so on), and your own ability to cope with the stress of fire situations. For example, if you live near the coast and have prepared your home well, you may wish to stay in all but extreme fire danger. If you live in bushland and do not feel that your home can be defended, you may wish to leave early.

Note

Remember, leaving a high-risk bushfire location is the safest action, and leaving before a bushfire threatens is always safer than remaining until a bushfire starts. Leaving becomes increasingly appropriate with higher Fire Danger Ratings. Work out your safest exit route before the fire season.

During a bushfire, it is crucial that you stay up to date on fire activity in your area. Monitor media outlets or information from local fire services on websites, social networks (Facebook and Twitter), or free apps for your mobile phone. Note that during catastrophic conditions, even the best prepared homes are at risk, so monitoring the fire danger rating every day is essential during the fire season. If your power goes out, a bushfire is likely to be close and you should act immediately.

References and additional reading

- Australian Building Codes Board (2019), Editions of the National Construction Code

- Bradstock RA, Gill MA and Williams RJ (eds) (2012). Flammable Australia: fire regimes, biodiversity and ecosystems in a changing world, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria.

- Bryant C (2008). Understanding bushfire: Trends in deliberate vegetation fires in Australia. Issue 27 of Australian Institute of Criminology Technical and background paper series.

- Bushfire CRC (2009). Victorian 2009 bushfire research response [PDF].

- Clare Cousin Architects (2014). Perspective. Australia’s Black Saturday five years later [PDF].

- Commonwealth of Australia (2020). Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements Report.

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) (2020). State of the Climate 2020,

- Country Fire Authority (2012). Planning for bushfire Victoria: guidelines for meeting Victoria’s bushfire planning requirements [PDF].

- Dowdy A, Pepler A, Ashcroft L, Jones D and Braganza K (2018). Climate change impacts on weather and ocean hazards in Australasia: Bureau of Meteorology contribution to Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council discussion paper Climate Change and the Emergency Management Sector.

- Eco magazine (1985). How bushfires set houses alight – lessons from Ash Wednesday [PDF].

- NSW Rural Fire Service, Standards for asset protection zones [PDF]

- NSW Rural Fire Service (2006). Planning for bush fire protection: a guide for councils, planners, fire authorities and developers. [PDF]

- NSW Rural Fire Service (2019), Planning for bush fire protection: a guide for councils, planners, fire authorities and developers [PDF].

- Ramsay C and Rudolph L (2003). Landscape and building design for bushfire areas, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria.

- The Fifth Estate, How to design your house for fire resistance and sustainability.

- Victorian Building Authority, A guide to retrofit your home for better protection from a bushfire [PDF].

Learn more

- Read Adapting to climate change to see how you can design your home for increasing temperatures

- Explore Water to find ways to save and reuse water in your home

- Think about Design for climate to understand how to make your home work best for your region

- Read Condensation for more detail on insulating a bushfire-prone home

Authors

Principal author: Dr Grahame Douglas 2020